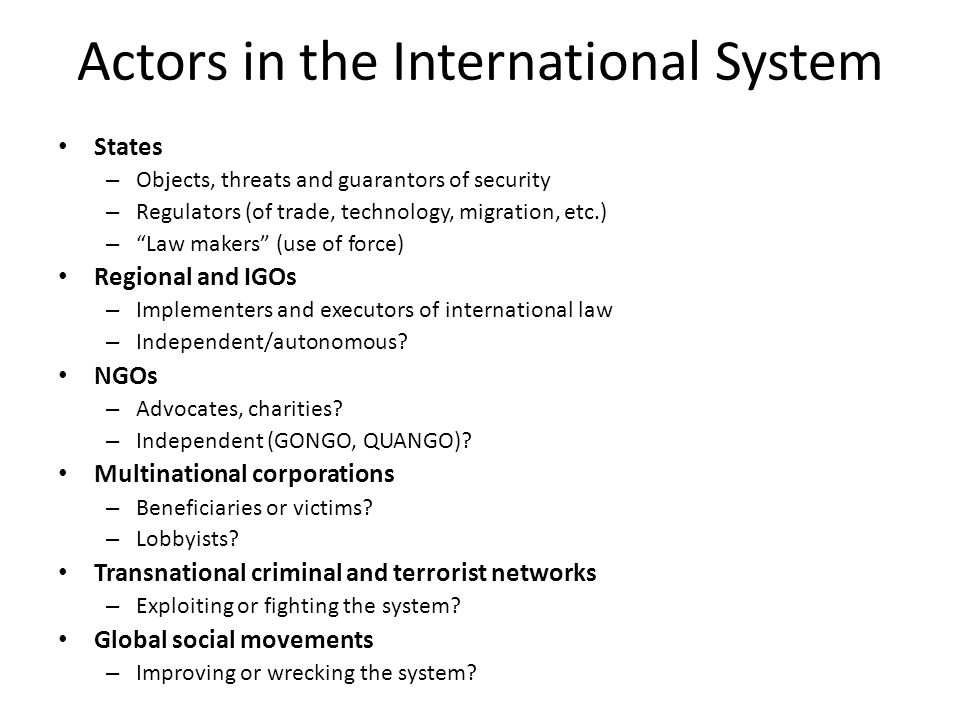

View Liberalism Theory Of International Relations PPTs online, safely and virus-free! Many are downloadable. Learn new and interesting things. The International Actors 4. International Behavior Space-Time 5. International Expectations And Dispositions 6. International Actor And Situation 7. International Sociocultural Space-Time 8. Interests, Capabilities, And Wills 9. The Social Field Of International Relations 10. Latent International Conflict 11. International Conflict: Trigger. Another important group of actors on the international stage are multinational enterprises (MNEs) - sometimes referred to as multinational corporations (MNCs). Multinational enterprises are. Viii International Relations Contents CONTRIBUTORS x GETTING STARTED 1 PART ONE - THE BASICS 1. THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD Erik Ringmar 8 2. DIPLOMACY Stephen McGlinchey 20 3. ONE WORLD, MANY ACTORS Carmen Gebhard 32 4. INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THEORY Dana Gold & Stephen McGlinchey 46 5. INTERNATIONAL LAW Knut Traisbach 57 6.

In the discipline of international relations there are contendinggeneral theories or theoretical perspectives. Realism, also known aspolitical realism, is a view of international politics that stressesits competitive and conflictual side. It is usually contrasted withidealism or liberalism, which tends to emphasize cooperation. Realistsconsider the principal actors in the international arena to be states,which are concerned with their own security, act in pursuit of theirown national interests, and struggle for power. The negative side ofthe realists’ emphasis on power and self-interest is often theirskepticism regarding the relevance of ethical norms to relations amongstates. National politics is the realm of authority and law, whereasinternational politics, they sometimes claim, is a sphere withoutjustice, characterized by active or potential conflict amongstates.

Not all realists, however, deny the presence of ethics ininternational relations. The distinction should be drawn betweenclassical realism—represented by such twentieth-century theoristsas Reinhold Niebuhr and Hans Morgenthau—and radical or extremerealism. While classical realism emphasizes the concept of nationalinterest, it is not the Machiavellian doctrine “that anything isjustified by reason of state” (Bull 1995, 189). Nor does itinvolve the glorification of war or conflict. The classical realists donot reject the possibility of moral judgment in international politics.Rather, they are critical of moralism—abstract moral discoursethat does not take into account political realities. They assignsupreme value to successful political action based on prudence: theability to judge the rightness of a given action from among possiblealternatives on the basis of its likely political consequences.

Realism encompasses a variety of approaches and claims a longtheoretical tradition. Among its founding fathers, Thucydides,Machiavelli and Hobbes are the names most usually mentioned.Twentieth-century classical realism has today been largely replaced byneorealism, which is an attempt to construct a more scientific approachto the study of international relations. Both classical realism andneorealism have been subjected to criticism from IR theoristsrepresenting liberal, critical, and post-modern perspectives.

- 1. The Roots of the Realist Tradition

- 2. Twentieth Century Classical Realism

- 3. Neorealism

1. The Roots of the Realist Tradition

1.1 Thucydides and the Importance of Power

Like other classical political theorists, Thucydides(c. 460–c. 400 B.C.E.) saw politics as involving moralquestions. Most importantly, he asks whether relations among states towhich power is crucial can also be guided by the norms ofjustice. His History of the Peloponnesian War is in factneither a work of political philosophy nor a sustained theory ofinternational relations. Much of this work, which presents a partialaccount of the armed conflict between Athens and Sparta that tookplace from 431 to 404 B.C.E., consists of paired speeches bypersonages who argue opposing sides of an issue. Nevertheless, ifthe History is described as the only acknowledged classicaltext in international relations, and if it inspires theorists fromHobbes to contemporary international relations scholars, this isbecause it is more than a chronicle of events, and a theoreticalposition can be extrapolated from it. Realism is expressed in the veryfirst speech of the Athenians recorded in theHistory—a speech given at the debate that took place inSparta just before the war. Moreover, a realist perspective is impliedin the way Thucydides explains the cause of the Peloponnesian War, andalso in the famous “Melian Dialogue,” in the statementsmade by the Athenian envoys.

1.1.1 General Features of Realism in International Relations

International relations realists emphasize the constraints imposedon politics by the nature of human beings, whom they consider egoistic,and by the absence of international government. Together these factorscontribute to a conflict-based paradigm of international relations, inwhich the key actors are states, in which power and security become themain issues, and in which there is little place for morality. The setof premises concerning state actors, egoism, anarchy, power, security,and morality that define the realist tradition are all present inThucydides.

(1) Human nature is a starting point for classical political realism. Realists view human beings as inherently egoistic and self-interested to the extent that self-interest overcomes moralprinciples. At the debate in Sparta, described in Book I ofThucydides’ History, the Athenians affirm the priorityof self-interest over morality. They say that considerations of rightand wrong have “never turned people aside from the opportunitiesof aggrandizement offered by superior strength” (chap. 1 par.76).

(2) Realists, and especially today’s neorealists, consider theabsence of government, literally anarchy, to be the primarydeterminant of international political outcomes. The lack of a commonrule-making and enforcing authority means, they argue, that theinternational arena is essentially a self-help system. Each state isresponsible for its own survival and is free to define its owninterests and to pursue power. Anarchy thus leads to a situation inwhich power has the overriding role in shaping interstate relations. Inthe words of the Athenian envoys at Melos, without any common authoritythat can enforce order, “the independent states survive [only]when they are powerful” (5.97).

(3) Insofar as realists envision the world of states as anarchic,they likewise view security as a central issue. To attain security,states try to increase their power and engage in power-balancing forthe purpose of deterring potential aggressors. Wars are fought toprevent competing nations from becoming militarily stronger.Thucydides, while distinguishing between the immediate and underlyingcauses of the Peloponnesian War, does not see its real cause in any ofthe particular events that immediately preceded its outbreak. Heinstead locates the cause of the war in the changing distribution ofpower between the two blocs of Greek city-states: the Delian League,under the leadership of Athens, and the Peloponnesian League, under theleadership of Sparta. According to him, the growth of Athenian powermade the Spartans afraid for their security, and thus propelled theminto war (1.23).

(4) Realists are generally skeptical about the relevance of moralityto international politics. This can lead them to claim that there is noplace for morality in international relations, or that there is atension between demands of morality and requirements of successfulpolitical action, or that states have their own morality that isdifferent from customary morality, or that morality, if employed at all, is merelyused instrumentally to justify states’ conduct. A clear case ofthe rejection of ethical norms in relations among states can be foundin the “Melian Dialogue” (5.85–113). This dialogue relatesto the events of 416 B.C.E., when Athens invaded the island of Melos. TheAthenian envoys presented the Melians with a choice, destruction orsurrender, and from the outset asked them not to appeal to justice, butto think only about their survival. In the envoys’ words,“We both know that the decisions about justice are made in humandiscussions only when both sides are under equal compulsion, but whenone side is stronger, it gets as much as it can, and the weak mustaccept that” (5.89). To be “under equal compulsion”means to be under the force of law, and thus to be subjected to acommon lawgiving authority (Korab-Karpowicz 2006, 234). Since such anauthority above states does not exist, the Athenians argue that in thislawless condition of international anarchy, the only right is the rightof the stronger to dominate the weaker. They explicitly equate rightwith might, and exclude considerations of justice from foreignaffairs.

1.1.2 The “Melian Dialogue”—The First Realist-Idealist Debate

We can thus find strong support for a realist perspective in thestatements of the Athenians. The question remains, however, to whatextent their realism coincides with Thucydides’ own viewpoint.Although substantial passages of the “Melian Dialogue,” aswell as other parts of the History support a realisticreading, Thucydides’ position cannot be deduced from suchselected fragments, but rather must be assessed on the basis of thewider context of his book. In fact, even the “MelianDialogue” itself provides us with a number of contendingviews.

Political realism is usually contrasted by IR scholars with idealismor liberalism, a theoretical perspective that emphasizes internationalnorms, interdependence among states, and international cooperation. The“Melian Dialogue,” which is one of the most frequentlycommented-upon parts of Thucydides’ History, presentsthe classic debate between the idealist and realist views: Caninternational politics be based on a moral order derived from theprinciples of justice, or will it forever remain the arena ofconflicting national interests and power?

For the Melians, who employ idealistic arguments, the choice isbetween war and subjection (5.86). They are courageous and love theircountry. They do not wish to lose their freedom, and in spite of thefact that they are militarily weaker than the Athenians, they areprepared to defend themselves (5.100; 5.112). They base their argumentson an appeal to justice, which they associate with fairness, and regardthe Athenians as unjust (5.90; 5.104). They are pious, believing thatgods will support their just cause and compensate for their weakness,and trust in alliances, thinking that their allies, the Spartans, whoare also related to them, will help them (5.104; 5.112). Hence, one canidentify in the speech of the Melians elements of the idealistic orliberal world view: the belief that nations have the right to exercisepolitical independence, that they have mutual obligations to oneanother and will carry out such obligations, and that a war ofaggression is unjust. What the Melians nevertheless lack are resourcesand foresight. In their decision to defend themselves, they are guidedmore by their hopes than by the evidence at hand or by prudentcalculations.

The Athenian argument is based on key realist concepts such assecurity and power, and is informed not by what the world should be,but by what it is. The Athenians disregard any moral talk and urge theMelians to look at the facts—that is, to recognize their militaryinferiority, to consider the potential consequences of their decision,and to think about their own survival (5.87; 5.101). There appears tobe a powerful realist logic behind the Athenian arguments. Theirposition, based on security concerns and self-interest, seeminglyinvolves reliance on rationality, intelligence, and foresight. However,upon close examination, their logic proves to be seriously flawed.Melos, a relatively weak state, does not pose any real security threatto them. The eventual destruction of Melos does not change the courseof the Peloponnesian War, which Athens will lose a few years later.

In the History, Thucydides shows that power, if it isunrestrained by moderation and a sense of justice, brings about theuncontrolled desire for more power. There are no logical limits to thesize of an empire. Drunk with the prospect of glory and gain, afterconquering Melos, the Athenians engage in a war against Sicily. Theypay no attention to the Melian argument that considerations of justiceare useful to all in the longer run (5.90). And, as the Atheniansoverestimate their strength and in the end lose the war, theirself-interested logic proves to be very shortsighted indeed.

It is utopian to ignore the reality of power in internationalrelations, but it is equally blind to rely on power alone. Thucydidesappears to support neither the naive idealism of the Melians nor thecynicism of their Athenian opponents. He teaches us to be on guard“against naïve-dreaming on international politics,”on the one hand, and “against the other pernicious extreme:unrestrained cynicism,” on the other (Donnelly 2000, 193). If hecan be regarded as a political realist, his realism nonetheless prefigures neither realpolitik, in which traditionalethics is denied, nor today’s scientific neorealism, in which moralquestions are largely ignored. Thucydides’ realism, neither immoralnor amoral, can rather be compared to that of Hans Morgenthau, RaymondAron, and other twentieth-century classical realists, who, althoughsensible to the demands of national interest, would not deny thatpolitical actors on the international scene are subject to moraljudgment.

1.2 Machiavelli’s Critique of the Moral Tradition

Idealism in international relations, like realism, can lay claim toa long tradition. Unsatisfied with the world as they have found it,idealists have always tried to answer the question of “what oughtto be” in politics. Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero were allpolitical idealists who believed that there were some universal moralvalues on which political life could be based. Building on the work ofhis predecessors, Cicero developed the idea of a natural moral law thatwas applicable to both domestic and international politics. His ideasconcerning righteousness in war were carried further in the writings ofthe Christian thinkers St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas. In thelate fifteenth century, when Niccolò Machiavelli was born, theidea that politics, including the relations among states, should bevirtuous, and that the methods of warfare should remain subordinated toethical standards, still predominated in political literature.

Machiavelli (1469–1527) challenged this well-established moraltradition, thus positioning himself as a political innovator. Thenovelty of his approach lies in his critique of classical Westernpolitical thought as unrealistic, and in his separation of politicsfrom ethics. He thereby lays the foundations for modern politics. Inchapter XV of The Prince, Machiavelli announces that indeparting from the teachings of earlier thinkers, he seeks “theeffectual truth of the matter rather than the imagined one.” The“effectual truth” is for him the only truth worth seeking.It represents the sum of the practical conditions that he believes arerequired to make both the individual and the country prosperous andstrong. Machiavelli replaces the ancient virtue (a moralquality of the individual, such as justice or self-restraint) withvirtù, ability or vigor. As a prophet ofvirtù, he promises to lead both nations and individualsto earthly glory and power.

Machiavellianism is a radical type of political realismthat is applied to both domestic and international affairs. It is adoctrine which denies the relevance of morality in politics, and claimsthat all means (moral and immoral) are justified to achieve certainpolitical ends. Although Machiavelli never uses the phrase ragionedi stato or its French equivalent, raisond’état, what ultimately counts for him is preciselythat: whatever is good for the state, rather than ethical scruples ornorms

Machiavelli justified immoral actions in politics, but never refusedto admit that they are evil. He operated within the single framework oftraditional morality. It became a specific task of hisnineteenth-century followers to develop the doctrine of a doubleethics: one public and one private, to push Machiavellian realism toeven further extremes, and to apply it to international relations. Byasserting that “the state has no higher duty than of maintainingitself,” Hegel gave an ethical sanction to the state’spromotion of its own interest and advantage against other states(Meinecke 357). Thus he overturned the traditional morality. The goodof the state was perversely interpreted as the highest moral value,with the extension of national power regarded as a nation’s rightand duty. Referring to Machiavelli, Heinrich von Treitschke declaredthat the state was power, precisely in order to assert itself asagainst other equally independent powers, and that the supreme moralduty of the state was to foster this power. He considered internationalagreements to be binding only insofar as it was expedient for thestate. The idea of an autonomous ethics of state behavior and theconcept of realpolitik were thus introduced. Traditionalethics was denied and power politics was associated with a“higher” type of morality. These concepts, along with thebelief in the superiority of Germanic culture, served as weapons withwhich German statesmen, from the eighteenth century to the end of theSecond World War, justified their policies of conquest andextermination.

Machiavelli is often praised for his prudential advice toleaders (which has caused him to be regarded as a founding master ofmodern political strategy) and for his defense of the republican formof government. There are certainly many aspects of his thought thatmerit such praise. Nevertheless, it is also possible to see him as thethinker who bears foremost responsibility for the demoralization of Europe.The argument of the Athenian envoys presented in Thucydides’“Melian Dialogue,” that of Thrasymachus in Plato’sRepublic, or that of Carneades, to whom Cicerorefers—all of these challenge the ancient and Christian views ofthe unity of politics and ethics. However, before Machiavelli, thisamoral or immoral mode of thinking had never prevailed in themainstream of Western political thought. It was the force andtimeliness of his justification of resorting to evil as a legitimatemeans of achieving political ends that persuaded so many of thethinkers and political practitioners who followed him. The effects ofMachiavellian ideas, such as the notion that the employment of allpossible means was permissible in war, would be seen on thebattlefields of modern Europe, as mass citizen armies fought againsteach other to the bitter end without regard for the rules of justice.The tension between expediency and morality lost its validity in thesphere of politics. The concept of a double ethics, private and public,that created a further damage to traditional, customary ethics wasinvented. The doctrine of raison d’étatultimately led to the politics of Lebensraum, two world wars,and the Holocaust.

Perhaps the greatest problem with realism in internationalrelations is that it has a tendency to slip into its extreme version,which accepts any policy that can benefit the state at the expense ofother states, no matter how morally problematic the policy is. Even ifthey do not explicitly raise ethical questions, in the works of Waltzand of many other of today’s neorealists, a double ethics ispresupposed, and words such realpolitik no longer have thenegative connotations that they had for classical realists, such asHans Morgenthau.

1.3 Hobbes’s Anarchic State of Nature

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1683) was part of an intellectual movement whosegoal was to free the emerging modern science from the constraints ofthe classical and scholastic heritage. According to classical politicalphilosophy, on which the idealist perspective is based, human beingscan control their desires through reason and can work for the benefitof others, even at the expense of their own benefit. They are thus bothrational and moral agents, capable of distinguishing between right andwrong, and of making moral choices. They are also naturally social.With great skill Hobbes attacks these views. His human beings,extremely individualistic rather than moral or social, are subject to“a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, thatceases only in death” (Leviathan XI 2). They thereforeinevitably struggle for power. In setting out such ideas, Hobbescontributes to some of the basic conceptions fundamental to the realisttradition in international relations, and especially to neorealism.These include the characterization of human nature as egoistic, theconcept of international anarchy, and the view that politics, rooted inthe struggle for power, can be rationalized and studiedscientifically.

One of the most widely known Hobbesian concepts is that of theanarchic state of nature, seen as entailing a state of war—and“such a war as is of every man against every man” (XII 8).He derives his notion of the state of war from his views of both humannature and the condition in which individuals exist. Since in the stateof nature there is no government and everyone enjoys equal status,every individual has a right to everything; that is, there are noconstraints on an individual’s behavior. Anyone may at any timeuse force, and all must constantly be ready to counter such force withforce. Hence, driven by acquisitiveness, having no moral restraints,and motivated to compete for scarce goods, individuals are apt to“invade” one another for gain. Being suspicious of oneanother and driven by fear, they are also likely to engage inpreemptive actions and invade one another to ensure their own safety.Finally, individuals are also driven by pride and a desire for glory.Whether for gain, safety, or reputation, power-seeking individuals willthus “endeavor to destroy or subdue one another” (XIII 3).In such uncertain conditions where everyone is a potential aggressor,making war on others is a more advantageous strategy than peaceablebehavior, and one needs to learn that domination over others isnecessary for one’s own continued survival.

Hobbes is primarily concerned with the relationship betweenindividuals and the state, and his comments about relations amongstates are scarce. Nevertheless, what he says about the lives ofindividuals in the state of nature can also be interpreted as adescription of how states exist in relation to one another. Once statesare established, the individual drive for power becomes the basis forthe states’ behavior, which often manifests itself in theirefforts to dominate other states and peoples. States, “for theirown security,” writes Hobbes, “enlarge their dominions uponall pretences of danger and fear of invasion or assistance that may begiven to invaders, [and] endeavour as much as they can, to subdue andweaken their neighbors” (XIX 4). Accordingly, the quest andstruggle for power lies at the core of the Hobbesian vision ofrelations among states. The same would later be true of the model ofinternational relations developed by Hans Morgenthau, who was deeplyinfluenced by Hobbes and adopted the same view of human nature.Similarly, the neorealist Kenneth Waltz would follow Hobbes’ leadregarding international anarchy (the fact that sovereign states are notsubject to any higher common sovereign) as the essential element ofinternational relations.

By subjecting themselves to a sovereign, individuals escape the warof all against all which Hobbes associates with the state of nature;however, this war continues to dominate relations among states. Thisdoes not mean that states are always fighting, but rather that theyhave a disposition to fight (XIII 8). With each state deciding foritself whether or not to use force, war may break out at any time. Theachievement of domestic security through the creation of a state isthen paralleled by a condition of inter-state insecurity. One can arguethat if Hobbes were fully consistent, he would agree with the notionthat, to escape this condition, states should also enter into acontract and submit themselves to a world sovereign. Although the ideaof a world state would find support among some of today’srealists, this is not a position taken by Hobbes himself. He does notpropose that a social contract among nations be implemented to bringinternational anarchy to an end. This is because the condition ofinsecurity in which states are placed does not necessarily lead toinsecurity for their citizens. As long as an armed conflict or other typeof hostility between states does not actually break out, individualswithin a state can feel relatively secure.

The denial of the existence of universal moral principles in therelations among states brings Hobbes close to the Machiavellians andthe followers of the doctrine of raison d’état.His theory of international relations, which assumes that independentstates, like independent individuals, are enemies by nature, asocialand selfish, and that there is no moral limitation on their behavior,is a great challenge to the idealist political vision based on humansociability and to the concept of the international jurisprudence thatis built on this vision. However, what separates Hobbes fromMachiavelli and associates him more with classical realism is hisinsistence on the defensive character of foreign policy. His politicaltheory does not put forward the invitation to do whatever may beadvantageous for the state. His approach to international relations isprudential and pacific: sovereign states, like individuals, should bedisposed towards peace which is commended by reason.

What Waltz and other neorealist readers of Hobbes’s workssometimes overlook is that he does not perceive international anarchyas an environment without any rules. By suggesting that certaindictates of reason apply even in the state of nature, he affirms thatmore peaceful and cooperative international relations are possible.Neither does he deny the existence of international law. Sovereignstates can sign treaties with one another to provide a legal basis fortheir relations. At the same time, however, Hobbes seems aware thatinternational rules will often prove ineffective in restraining thestruggle for power. States will interpret them to their own advantage,and so international law will be obeyed or ignored according to theinterests of the states affected. Hence, international relations willalways tend to be a precarious affair. This grim view of globalpolitics lies at the core of Hobbes’s realism.

2. Twentieth Century Classical Realism

Twentieth-century realism was born in response to the idealistperspective that dominated international relations scholarship in theaftermath of the First World War. The idealists of the 1920s and 1930s(also called liberal internationalists or utopians) had the goal ofbuilding peace in order to prevent another world conflict. They saw thesolution to inter-state problems as being the creation of a respectedsystem of international law, backed by international organizations.This interwar idealism resulted in the founding of the League ofNations in 1920 and in the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 outlawing warand providing for the peaceful settlements of disputes. U.S. PresidentWoodrow Wilson, scholars such as Norman Angell, Alfred Zimmern, andRaymond B. Fosdick, and other prominent idealists of the era, gavetheir intellectual support to the League of Nations. Instead offocusing on what some might see as the inevitability of conflictbetween states and peoples, they chose to emphasize the commoninterests that could unite humanity, and attempted to appeal torationality and morality. For them, war did not originate in anegoistic human nature, but rather in imperfect social conditions andpolitical arrangements, which could be improved. Yet their ideas werealready being criticized in the early 1930s by Reinhold Niebuhr andwithin a few years by E. H. Carr. The League of Nations, which theUnited States never joined, and from which Japan and Germany withdrew,could not prevent the outbreak of the Second World War. This fact,perhaps more than any theoretical argument, produced a strong realistreaction. Although the United Nations, founded in 1945, can still beregarded as a product of idealist political thinking, the discipline ofinternational relations was profoundly influenced in the initial yearsof the post-war period by the works of “classical” realistssuch as John H. Herz, Hans Morgenthau, George Kennan, and Raymond Aron.Then, during the 1950s and 1960s, classical realism came underchallenge of scholars who tried to introduce a more scientific approachto the study of international politics. During the 1980s it gave way toanother trend in international relations theory—neorealism.

Since it is impossible within the scope of this article to introduceall of the thinkers who contributed to the development oftwentieth-century classical realism, E. H. Carr and Hans Morgenthau, asperhaps the most influential among them, have been selected fordiscussion here.

2.1 E. H. Carr’s Challenge to Utopian Idealism

In his main work on international relations, The TwentyYears’ Crisis, first published in July 1939, Edward HallettCarr (1892–1982) attacks the idealist position, which he describes as“utopianism.” He characterizes this position asencompassing faith in reason, confidence in progress, a sense of moralrectitude, and a belief in an underlying harmony of interests.According to the idealists, war is an aberration in the course ofnormal life and the way to prevent it is to educate people for peace,and to build systems of collective security such as the League ofNations or today’s United Nations. Carr challenges idealism byquestioning its claim to moral universalism and its idea of the harmonyof interests. He declares that “morality can only be relative,not universal” (19), and states that the doctrine of the harmonyof interests is invoked by privileged groups “to justify andmaintain their dominant position” (75).

Carr uses the concept of the relativity of thought, which he tracesto Marx and other modern theorists, to show that standards by whichpolicies are judged are the products of circumstances and interests.His central idea is that the interests of a given party alwaysdetermine what this party regards as moral principles, and hence, theseprinciples are not universal. Carr observes that politicians, forexample, often use the language of justice to cloak the particularinterests of their own countries, or to create negative images of otherpeople to justify acts of aggression. The existence of such instancesof morally discrediting a potential enemy or morally justifyingone’s own position shows, he argues, that moral ideas are derivedfrom actual policies. Policies are not, as the idealists would have it,based on some universal norms, independent of interests of the partiesinvolved.

If specific moral standards are de facto founded on interests,Carr’s argument goes, there are also interests underlying whatare regarded as absolute principles or universal moral values. Whilethe idealists tend to regard such values, such as peace or justice, asuniversal and claim that upholding them is in the interest of all, Carrargues against this view. According to him, there are neither universalvalues nor universal interests. He claims that those who refer to universalinterests are in fact acting in their own interests (71). They think that what is best for them is best for everyone, and identify their owninterests with the universal interest of the world at large.

The idealist concept of the harmony of interests is basedon the notion that human beings can rationally recognize that they havesome interests in common, and that cooperation is therefore possible.Carr contrasts this idea with the reality of conflict ofinterests. According to him, the world is torn apart by theparticular interests of different individuals and groups. In such aconflictual environment, order is based on power, not on morality.Further, morality itself is the product of power (61). Like Hobbes,Carr regards morality as constructed by the particular legal systemthat is enforced by a coercive power. International moral norms areimposed on other countries by dominant nations or groups of nationsthat present themselves as the international community as a whole. Theyare invented to perpetuate those nations’ dominance.

Values that idealists view as good for all, such as peace, socialjustice, prosperity, and international order, are regarded by Carr asmere status quo notions. The powers that are satisfied withthe status quo regard the arrangement in place as just and thereforepreach peace. They try to rally everyone around their idea of what isgood. “Just as the ruling class in a community prays for domesticpeace, which guarantees its own security and predominance, … sointernational peace becomes a special vested interest of predominantpowers” (76). On the other hand, the unsatisfied powers considerthe same arrangement as unjust, and so prepare for war. Hence, the wayto obtain peace, if it cannot be simply enforced, is to satisfy theunsatisfied powers. “Those who profit most by [international]order can in the longer run only hope to maintain it by makingsufficient concessions to make it tolerable to those who profit by itleast” (152). The logical conclusion to be drawn by the reader ofCarr’s book is the policy of appeasement.

Carr was a sophisticated thinker. He recognized himself that the logicof “pure realism can offer nothing but a naked struggle forpower which makes any kind of international society impossible”(87). Although he demolishes what he calls “the currentutopia” of idealism, he at the same time attempts to build“a new utopia,” a realist world order(ibid.). Thus, he acknowledges that human beings need certainfundamental, universally acknowledged norms and values, andcontradicts his own argument by which he tries to deny universality toany norms or values. To make further objections, the fact that thelanguage of universal moral values can be misused in politics for thebenefit of one party or another, and that such values can only beimperfectly implemented in political institutions, does not mean thatsuch values do not exist. There is a deep yearning in many humanbeings, both privileged and unprivileged, for peace, order,prosperity, and justice. The legitimacy of idealism consists in theconstant attempt to reflect upon and uphold these values. Idealistsfail if in their attempt they do not pay enough attention to thereality of power. On the other hand, in the world of pure realism, inwhich all values are made relative to interests, life turns intonothing more than a power game and is unbearable.

The Twenty Years’ Crisis touches on a number ofuniversal ideas, but it also reflects the spirit of its time. While wecan fault the interwar idealists for their inability to constructinternational institutions strong enough to prevent the outbreak of theSecond World War, this book indicates that interwar realists werelikewise unprepared to meet the challenge. Carr frequently refers toGermany under Nazi rule as if it were a country like any other. He saysthat should Germany cease to be an unsatisfied power and “becomesupreme in Europe,” it would adopt a language of internationalsolidarity similar to that of other Western powers (79). The inabilityof Carr and other realists to recognize the perilous nature of Nazism,and their belief that Germany could be satisfied by territorialconcessions, helped to foster a political environment in which thelatter was to grow in power, annex Czechoslovakia at will, and bemilitarily opposed in September 1939 by Poland alone.

A theory of international relations is not just an intellectualenterprise; it has practical consequences. It influences our thinkingand political practice. On the practical side, the realists of the1930s, to whom Carr gave intellectual support, were people opposed tothe system of collective security embodied in the League of Nations.Working within the foreign policy establishments of the day, theycontributed to its weakness. Once they had weakened the League, theypursued a policy of appeasement and accommodation with Germany as analternative to collective security (Ashworth 46). After the annexationof Czechoslovakia, when the failure of the anti-League realistconservatives gathered around Neville Chamberlain and of this policybecame clear, they tried to rebuild the very security system they hadearlier demolished. Those who supported collective security werelabeled idealists.

2.2 Hans Morgenthau’s Realist Principles

Hans J. Morgenthau (1904–1980) developed realism into acomprehensive international relations theory. Influenced by theProtestant theologian and political writer Reinhold Niebuhr, as well asby Hobbes, he places selfishness and power-lust at the center of hispicture of human existence. The insatiable human lust for power,timeless and universal, which he identifies with animusdominandi, the desire to dominate, is for him the main cause ofconflict. As he asserts in his main work, Politics among Nations:The Struggle for Power and Peace, first published in 1948,“international politics, like all politics, is a struggle forpower” (25).

Morgenthau systematizes realism in international relations on thebasis of six principles that he includes in the second edition ofPolitics among Nations. As a traditionalist, he opposesthe so-called scientists (the scholars who, especially in the1950s, tried to reduce the discipline of international relations to abranch of behavioral science). Nevertheless, in the first principle he states thatrealism is based on objective laws that have their roots in unchanginghuman nature (4). He wants to develop realism into both a theory ofinternational politics and a political art, a useful tool of foreignpolicy.

The keystone of Morgenthau’s realist theory is the conceptof power or “of interest defined in terms of power,”which informs his second principle: the assumption that politicalleaders “think and act in terms of interest defined aspower” (5). This concept defines the autonomy of politics, andallows for the analysis of foreign policy regardless of the differentmotives, preferences, and intellectual and moral qualities ofindividual politicians. Furthermore, it is the foundation of a rationalpicture of politics.

Although, as Morgenthau explains in the third principle, interestdefined as power is a universally valid category, and indeed anessential element of politics, various things can be associated withinterest or power at different times and in different circumstances.Its content and the manner of its use are determined by the politicaland cultural environment.

In the fourth principle, Morgenthau considers the relationship betweenrealism and ethics. He says that while realists are aware of the moralsignificance of political action, they are also aware of the tensionbetween morality and the requirements of successful politicalaction. “Universal moral principles,” he asserts,“cannot be applied to the actions of states in their abstractuniversal formulation, but …they must be filtered through theconcrete circumstances of time and place” (9). These principlesmust be accompanied by prudence for as he cautions “there can beno political morality without prudence; that is, without considerationof the political consequences of seemingly moral action”(ibid.).

Prudence, and not conviction of one’s own moral or ideologicalsuperiority, should guide political action. This is stressed in thefifth principle, where Morgenthau again emphasizes the idea that allstate actors, including our own, must be looked at solely as politicalentities pursuing their respective interests defined in terms of power.By taking this point of view vis-à-vis its counterparts and thusavoiding ideological confrontation, a state would then be able topursue policies that respected the interests of other states, whileprotecting and promoting its own.

Insofar as power, or interest defined as power, is the concept thatdefines politics, politics is an autonomous sphere, as Morgenthau saysin his sixth principle of realism. It cannot be subordinated to ethics.However, ethics does still play a role in politics. “A man whowas nothing but ‘political man’ would be a beast, for hewould be completely lacking in moral restraints. A man who was nothingbut ‘moral man’ would be a fool, for he would be completelylacking in prudence” (12). Political art requires that these twodimensions of human life, power and morality, be taken intoconsideration.

While Morgenthau’s six principles of realism containrepetitions and inconsistencies, we can nonetheless obtain from themthe following picture: Power or interest is the central concept thatmakes politics into an autonomous discipline. Rational state actorspursue their national interests. Therefore, a rational theory ofinternational politics can be constructed. Such a theory is notconcerned with the morality, religious beliefs, motives or ideologicalpreferences of individual political leaders. It also indicates that inorder to avoid conflicts, states should avoid moral crusades orideological confrontations, and look for compromise based solely onsatisfaction of their mutual interests.

Although he defines politics as an autonomous sphere, Morgenthaudoes not follow the Machiavellian route of completely removing ethicsfrom politics. He suggests that, although human beings are politicalanimals, who pursue their interests, they are moral animals. Deprivedof any morality, they would descend to the level of beasts orsub-humans. Even if it is not guided by universal moral principles,political action thus has for Morgenthau a moral significance.Ultimately directed toward the objective of national survival, it alsoinvolves prudence. The effective protection of citizens’ livesfrom harm is not merely a forceful physical action; it has prudentialand moral dimensions.

Morgenthau regards realism as a way of thinking about internationalrelations and a useful tool for devising policies. However, some of thebasic conceptions of his theory, and especially the idea of conflict asstemming from human nature, as well as the concept of power itself,have provoked criticism.

International politics, like all politics, is for Morgenthau astruggle for power because of the basic human lust for power. Butregarding every individual as being engaged in a perpetual quest forpower—the view that he shares with Hobbes—is a questionable premise. Human nature cannot be revealed by observation and experiment. It cannot be proved by any empirical research, but only disclosed by philosophy, imposed on us as a matter of belief, and inculcated by education.

Morgenthau himself reinforces the belief in the human drive for power by introducing a normative aspect of his theory, which is rationality. A rational foreign policyis considered “to be a good foreign policy” (7). But he defines rationality as a process of calculating the costs and benefits of all alternative policies in order to determine their relativeutility, i.e. their ability to maximize power. Statesmen “thinkand act in terms of interest defined as power” (5). Onlyintellectual weakness of policy makers can result in foreign policiesthat deviate from a rational course aimed at minimizing risks andmaximizing benefits. Hence, rather than presenting an actual portrait of humanaffairs, Morgenthau emphasizes the pursuit of power and the rationality of this pursuit, and sets it up as a norm.

As Raymond Aron and other scholars have noticed, power, thefundamental concept of Morgenthau’s realism, is ambiguous. It canbe either a means or an end in politics. But if power is only a meansfor gaining something else, it does not define the nature ofinternational politics in the way Morgenthau claims. It does not allowus to understand the actions of states independently from the motivesand ideological preferences of their political leaders. It cannot serveas the basis for defining politics as an autonomous sphere.Morgenthau’s principles of realism are thus open to doubt.“Is this true,” Aron asks, “that states, whatevertheir regime, pursue the same kind of foreign policy” (597) andthat the foreign policies of Napoleon or Stalin are essentiallyidentical to those of Hitler, Louis XVI or Nicholas II, amounting to nomore than the struggle for power? “If one answers yes, then theproposition is incontestable, but not very instructive” (598).Accordingly, it is useless to define actions of states by exclusivereference to power, security or national interest. Internationalpolitics cannot be studied independently of the wider historical andcultural context.

Although Carr and Morgenthau concentrate primarily on internationalrelations, their realism can also be applied to domestic politics. Tobe a classical realist is in general to perceive politics as a conflict ofinterests and a struggle for power, and to seek peace by recognizing common interests and trying to satisfy them, rather than by moralizing. Bernard Williams and Raymond Geuss, influential representatives of the new political realism, a movement in contemporary political theory, criticize what they describe as “political moralism” and stress the autonomy of politics against ethics. However, political theory realism and international relations realism seem like two separate research programs. As noted by several scholars (William Scheuerman, Alison McQueen, Terry Nardin. Duncan Bell), those who contribute to realism in political theory give little attention to those who work on realism in international politics.

3. Neorealism

In spite of its ambiguities and weaknesses, Morgenthau’sPolitics among Nations became a standard textbook andinfluenced thinking about international politics for a generation orso. At the same time, there was an attempt to develop a more methodologically rigorous approach to theorizing about international affairs. In the 1950s and 1960s a large influx of scientists from different fields entered the discipline of International Relations and attempted to replace the “wisdom literature” of classical realists with scientific concepts and reasoning (Brown 35). This in turn provoked a counterattack by Morgenthau and scholars associated with the so-called English School, especially Hedley Bull, who defended a traditional approach (Bull 1966).

As a result, the IR discipline has been divided into two main strands: traditional or non-positivist and scientific or positivist (neo-positivist). At a later stage the third strand: post-positivism has been added. The traditionalists raise normative questions and engage with history, philosophy and law. The scientists or positivists stress a descriptive and explanatory form of inquiry, rather than a normative one. They have established a strong presence in the field. Already by the mid-1960s, the majority of American students in international relations were trained in quantitative research, game theory, and other new research techniques of the social sciences. This, along with the changing international environment, had a significant effect on the discipline.

The realist assumption was that the state is the key actor in international politics, and that relations among states are the core of actual international relations. However, with the receding of the Cold War during the 1970s, one could witness the growing importance of international and non-governmental organizations, as well as of multinational corporations. This development led to a revival of idealist thinking, which became known as neoliberalism or pluralism. While accepting some basic assumptions of realism, the leading pluralists, Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, have proposed the concept ofcomplex interdependence to describe this more sophisticated picture of global politics. They would argue that there can be progress in international relations and that the future does not need to look like the past.

3.1 Kenneth Waltz’s International System

The realist response came most prominently from Kenneth N. Waltz,who reformulated realism in international relations in a new anddistinctive way. In his book Theory of International Politics,first published in 1979, he responded to the liberal challenge andattempted to cure the defects of the classical realism of HansMorgenthau with his more scientific approach, which has became known asstructural realism or neorealism. Whereas Morgenthau rooted his theoryin the struggle for power, which he related to human nature, Waltz madean effort to avoid any philosophical discussion of human nature, andset out instead to build a theory of international politics analogousto microeconomics. He argues that states in the international systemare like firms in a domestic economy and have the same fundamentalinterest: to survive. “Internationally, the environment ofstates’ actions, or the structure of their system, is set by thefact that some states prefer survival over other ends obtainable in theshort run and act with relative efficiency to achieve that end”(93).

Waltz maintains that by paying attention to the individual state,and to ideological, moral and economic issues, both traditionalliberals and classical realists make the same mistake. They fail todevelop a serious account of the international system—one thatcan be abstracted from the wider socio-political domain. Waltzacknowledges that such an abstraction distorts reality and omits manyof the factors that were important for classical realism. It does notallow for the analysis of the development of specific foreign policies.However, it also has utility. Notably, it assists in understanding theprimary determinants of international politics. To be sure, Waltz’sneorealist theory cannot be applied to domestic politics. It cannotserve to develop policies of states concerning their international ordomestic affairs. His theory helps only to explain why states behave insimilar ways despite their different forms of government and diversepolitical ideologies, and why, despite their growinginterdependence, the overall picture of international relations isunlikely to change.

According to Waltz, the uniform behavior of states over centuriescan be explained by the constraints on their behavior that are imposedby the structure of the international system. A system’sstructure is defined first by the principle by which it is organized,then by the differentiation of its units, and finally by thedistribution of capabilities (power) across units. Anarchy, or theabsence of central authority, is for Waltz the ordering principle ofthe international system. The units of the international system arestates. Waltz recognizes the existence of non-state actors, butdismisses them as relatively unimportant. Since all states want tosurvive, and anarchy presupposes a self-help system in which each statehas to take care of itself, there is no division of labor or functionaldifferentiation among them. While functionally similar, they arenonetheless distinguished by their relative capabilities (the powereach of them represents) to perform the same function.

Consequently, Waltz sees power and state behavior in a different wayfrom the classical realists. For Morgenthau power was both a means andan end, and rational state behavior was understood as simply thecourse of action that would accumulate the most power. In contrast,neorealists assume that the fundamental interest of each state issecurity and would therefore concentrate on the distribution of power.What also sets neorealism apart from classical realism ismethodological rigor and scientific self-conception (Guzinni 1998,127–128). Waltz insists on empirical testability of knowledge and onfalsificationism as a methodological ideal, which, as he himselfadmits, can have only a limited application in internationalrelations.

The distribution of capabilities among states can vary; however,anarchy, the ordering principle of international relations, remainsunchanged. This has a lasting effect on the behavior of states thatbecome socialized into the logic of self-help. Trying to refuteneoliberal ideas concerning the effects of interdependence, Waltzidentifies two reasons why the anarchic international system limitscooperation: insecurity and unequal gains. In the context of anarchy,each state is uncertain about the intentions of others and is afraidthat the possible gains resulting from cooperation may favor otherstates more than itself, and thus lead it to dependence on others.“States do not willingly place themselves in situations ofincreased dependence. In a self-help system, considerations of securitysubordinate economic gain to political interest.” (Waltz 1979,107).

Because of its theoretical elegance and methodological rigor,neorealism has become very influential within the discipline ofinternational relations. In the eyes of many scholars, Morgenthau’srealism has come to be seen as anachronistic—“aninteresting and important episode in the history of thinking about thesubject, no doubt, but one scarcely to be seen as a seriouscontribution of the rigorously scientific theory” (Williams2007, 1). However, while initially gaining more acceptance thanclassical realism, neorealism has also provoked strong critiques on anumber of fronts.

3.2 Objections to Neorealism

In 1979 Waltz wrote that in the nuclear age the internationalbipolar system, based on two superpowers—the United States andthe Soviet Union—was not only stable but likely to persist(176–7). With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequentdisintegration of the USSR this prediction was proven wrong. Thebipolar world turned out to have been more precarious than most realistanalysts had supposed. Its end opened new possibilities and challengesrelated to globalization. This has led many critics to argue thatneorealism, like classical realism, cannot adequately account forchanges in world politics.

The new debate between international (neo)realists and (neo)liberalsis no longer concerned with the questions of morality and human nature,but with the extent to which state behavior is influenced by the anarchicstructure of the international system rather than by institutions, learning and other factors that are conductive to cooperation. In his 1989 book InternationalInstitutions and State Power, Robert Keohane accepts Waltz’semphasis on system-level theory and his general assumption that statesare self-interested actors that rationally pursue their goals. However,by employing game theory he shows that states can widen the perceptionof their self-interest through economic cooperation and involvement ininternational institutions. Patterns of interdependence can thus affectworld politics. Keohane calls for systemic theories that would be ableto deal better with factors affecting state interaction, and withchange.

Critical theorists, such as Robert W. Cox, also focus on the allegedinability of neorealism to deal with change. In their view,neorealists take a particular, historically determined state-basedstructure of international relations and assume it to be universallyvalid. In contrast, critical theorists believe that by analyzing theinterplay of ideas, material factors, and social forces, one canunderstand how this structure has come about, and how it mayeventually change. They contend that neorealism ignores both thehistorical process during which identities and interests are formed,and the diverse methodological possibilities. It legitimates theexisting status quo of strategic relations among states and considersthe scientific method as the only way of obtaining knowledge. Itrepresents an exclusionary practice, an interest in domination andcontrol.

While realists are concerned with relations among states, the focusfor critical theorists is social emancipation. Despite theirdifferences, critical theory, postmodernism and feminism all take issuewith the notion of state sovereignty and envision new politicalcommunities that would be less exclusionary vis-à-vis marginaland disenfranchised groups. Critical theory argues against state-basedexclusion and denies that the interests of a country’s citizenstake precedence over those of outsiders. It insists that politiciansshould give as much weight to the interests of foreigners as they giveto those of their compatriots and envisions political structures beyondthe “fortress” nation-state. Postmodernism questions thestate’s claim to be a legitimate focus of human loyalties and itsright to impose social and political boundaries. It supports culturaldiversity and stresses the interests of minorities. Feminism arguesthat the realist theory exhibits a masculine bias and advocates theinclusion of woman and alternative values into public life.

Since critical theories and other alternative theoretical perspectives question the existing status quo, make knowledge dependent on power, and emphasize identity formation and social change, they are not traditional or non-positivist. They are sometimes called “reflectivist” or “post-positivist” (Weaver 165) and represent a radical departure from the neorealist and neoliberal “rationalist” or “positivist” international relation theories. Constructivists, such as Alexander Wendt, try to build a bridge between these two approaches by on the one hand, taking the present state system and anarchy seriously, and on the other hand, by focusing on the formation of identities and interests. Countering neorealist ideas, Wendt argues that self-help does not follow logically or casually from the principle of anarchy. It is socially constructed. Wendt’s idea that states’ identities andinterests are socially constructed has earned his position the label“constructivism”. Consequently, in his view,“self-help and power politics are institutions, and not essentialfeatures of anarchy. Anarchy is what states make of it” (Wendt1987 395). There is no single logic of anarchy but rather several,depending on the roles with which states identify themselves and eachother. Power and interests are constituted by ideas and norms. Wendtclaims that neorealism cannot account for change in world politics, buthis norm-based constructivism can.

A similar conclusion, although derived in a traditional way, comesfrom the non-positivist theorists of the English school (International Societyapproach) who emphasize both systemic and normative constraints on thebehavior of states. Referring to the classical view of the human beingas an individual that is basically social and rational, capable ofcooperating and learning from past experiences, these theoristsemphasize that states, like individuals, have legitimate interests thatothers can recognize and respect, and that they can recognize thegeneral advantages of observing a principle of reciprocity in theirmutual relations (Jackson and Sørensen 167). Therefore, statescan bind themselves to other states by treaties and develop some commonvalues with other states. Hence, the structure of the internationalsystem is not unchangeable as the neorealists claim. It is not apermanent Hobbesian anarchy, permeated by the danger of war. Ananarchic international system based on pure power relations amongactors can evolve into a more cooperative and peaceful internationalsociety, in which state behavior is shaped by commonly shared valuesand norms. A practical expression of international society areinternational organizations that uphold the rule of law ininternational relations, especially the UN.

4. Conclusion: The Cautionary and Changing Character of Realism

An unintended and unfortunate consequence of the debate aboutneorealism is that neorealism and a large part of its critique (withthe notable exception of the English School) has been expressed in abstractscientific and philosophical terms. This has made the theory ofinternational politics almost inaccessible to a layperson and hasdivided the discipline of international relations into incompatibleparts. Whereas classical realism was a theory aimed at supportingdiplomatic practice and providing a guide to be followed by thoseseeking to understand and deal with potential threats, today’stheories, concerned with various grand pictures and projects, areill-suited to perform this task. This is perhaps the main reason whythere has been a renewed interest in classicalrealism, and particularly in the ideas of Morgenthau. Rather thanbeing seen as an obsolete form of pre-scientific realist thought,superseded by neorealist theory, his thinking is now considered to bemore complex and of greater contemporary relevance than wasearlier recognized (Williams 2007, 1–9). It fits uneasily in theorthodox picture of realism he is usually associated with.

In recent years, scholars have questioned prevailing narratives aboutclear theoretical traditions in the discipline of internationalrelations. Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes and other thinkers havebecome subject to re-examination as a means of challenging prevailinguses of their legacies in the discipline and exploring other lineagesand orientations. Morgenthau has undergone a similar process ofreinterpretation. A number of scholars (Hartmut Behr, Muriel Cozette, Amelia Heath, Sean Molloy) have endorsed the importance of his thought as a source of change for the standard interpretation of realism. Murielle Cozette stresses Morgenthau’s critical dimension ofrealism expressed in his commitment to “speak truth topower” and to “unmask power’s claims to truth and morality,” and in his tendency to assert different claims at different times (Cozette 10–12). She writes: “The protection of human life and freedom are given central importance by Morgenthau, and constitute a ‘transcendent standard of ethics’ which should always animate scientific enquiries” (19). This shows the flexibility of his classical realism and reveals his normative assumptions based on the promotion of universal moral values. While Morgenthau assumes that states are power-oriented actors, he at the same time acknowledges that international politics would be more pernicious than it actually is were it not for moral restraints and the work of international law(Behr and Heath 333).

Another avenue for the development of a realist theory of international relations is offered by Robert Gilpin’s seminal work War and Change in World Politics. If this work were to gain greater prominence in IR scholarship, instead of engaging in fruitless theoretical debates, we would be better prepared today “for rapid power shifts and geopolitical change ”(Wohlforth, 2011 505). We would be able to explain the causes of great wars and long periods of peace, and the creation and waning of international orders. Still another avenue is provided by the application of the new scientific discoveries to social sciences. The evidence for this is, for example, the recent work of Alexander Wendt, Quantum Mind and Social Science. A new realist approach to international politics could be based on the organic and holistic world view emerging from quantum theory, the idea of human evolution, and the growing awareness of the role of human beings in the evolutionary process (Korab-Karpowicz 2017).

Realism is thus more than a static, amoral theory, and cannot beaccommodated solely within a positivist interpretation of internationalrelations. It is a practical and evolving theory that depends on the actualhistorical and political conditions, and is ultimately judged by itsethical standards and by its relevance in making prudent politicaldecisions (Morgenthau 1962). Realism also performs a useful cautionaryrole. It warns us against progressivism, moralism, legalism, and otherorientations that lose touch with the reality of self-interest andpower. Considered from this perspective, the neorealist revival of the 1970s can also be interpreted as a necessary corrective to an overoptimistic liberal belief ininternational cooperation and change resulting frominterdependence.

Nevertheless, when it becomes a dogmatic enterprise, realism fails toperform its proper function. By remaining stuck in a state-centric andexcessively simplified “paradigm” such as neorealism and bydenying the possibility of any progress in interstate relations, itturns into an ideology. Its emphasis on power politics and nationalinterest can be misused to justify aggression. It has therefore to besupplanted by theories that take better account of the dramaticallychanging picture of global politics. To its merely negative,cautionary function, positive norms must be added. These norms extendfrom the rationality and prudence stressed by classical realists;through the vision of multilateralism, international law, and aninternational society emphasized by liberals and members of theEnglish School; to the cosmopolitanism and global solidarity advocatedby many of today’s writers.

Actors In International Relations Pdf

Bibliography

- Aron, Raymond, 1966. Peace and War: A Theory of InternationalRelations, trans. Richard Howard and Annette Baker Fox, GardenCity, New York: Doubleday.

- Ashley, Richard K., 1986. “The Poverty of Neorealism,” in Neorealism and Its Critics, Robert O. Keohane (ed.),New York: Columbia University Press, 255–300.

- –––, 1988. “Untying the Sovereign State: ADouble Reading of the Anarchy Problematique,” Millennium,17: 227–262.

- Ashworth, Lucian M., 2002. “Did the Realist-Idealist DebateReally Happen? A Revisionist History of International Relations,”International Relations, 16(1): 33–51.

- Brown, Chris, 2001. Understanding International Relations, 2nd edition, New York: Palgrave.

- Behr, Hartmut, 2010. A History of International Political Theory: Ontologies of the International, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Behr, Hartmut and Amelia Heath, 2009. “Misreading in IR Theory and Ideology Critique: Morgenthau, Waltz, and Neo-Realism,” Review of International Studies, 35(2): 327–349.

- Beitz, Charles, 1997. Political Theory and InternationalRelations, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bell, Duncan (ed.), 2008. Political Thought in InternationalRelations: Variations on a Realist Theme, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- –––, 2017. “Political Realism andInternational Relations,” Philosophy Compass, 12(2):e12403.

- Booth, Ken and Steve Smith (eds.), 1995. International RelationsTheory Today, Cambridge: Polity.

- Boucher, David, 1998. Theories of International Relations: FromThucydides to the Present, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bull, Hedley, 1962. “International Theory: The Case for Traditional Approach,” World Politics, 18(3): 361–377.

- –––, 1977. The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order inWorld Politics, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- –––, 1995. “The Theory of International Politics1919–1969,” in International Theory: Critical Investigations, J. Den Derian (ed.), London: MacMillan, 181–211.

- Butterfield, Herbert and Martin Wight (eds.), 1966. DiplomaticInvestigations: Essays in the Theory of International Politics,Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Carr, E. H., 2001. The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 1919–1939:An Introduction to Study International Relations, New York:Palgrave.

- Cawkwell, George, 1997. Thucydides and the PeloponnesianWar, London: Routledge.

- Cox, Robert W., 1986. “Social Forces, States and WorldOrders: Beyond International Relations Theory,”in Neorealism and Its Critics, Robert O. Keohane (ed.), NewYork: Columbia University Press, 204–254.

- Cozette, Muriel, 2008. “Reclaiming the Critical Dimension of Realism: Hans J. Morgenthau and the Ethics of Scholarship,” Review of International Studies, 34(1): 5–27.

- Der Derian, James (ed.), 1995. International Theory: CriticalInvestigations, London: Macmillan.

- Donnelly, Jack, 2000. Realism and International Relations,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Doyle, Michael W., 1997. Ways of War and Peace: Realism,Liberalism, and Socialism, New York: Norton.

- Galston, William A., 2010. “Realism in Political Theory,” European Journal of Political Theory, 9(4): 385–411.

- Geuss, Raymond, 2008. Philosophy and Real Politics, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gustafson, Lowell S. (ed.), 2000. Thucydides’ Theory ofInternational Relations, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UniversityPress.

- Guzzini, Stefano, 1998. Realism in International Relations andInternational Political Economy: The Continuing Story of a DeathForetold, London: Routledge.

- Harbour, Frances V., 1999. Thinking About InternationalEthics, Boulder: Westview.

- Herz, Thomas, 1951, Political Realism and Political Idealism: A Study of Theories and Realities, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hobbes, Thomas, 1994 (1660), Leviathan, Edwin Curley (ed.),Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Hoffman, Stanley, 1981. Duties Beyond Borders: On the Limitsand Possibilities of Ethical International Politics, Syracuse:Syracuse University Press.

- Jackson, Robert and Georg Sørensen, 2003. Introductionto International Relations: Theories and Approaches, Oxford:Oxford University Press.

- Kennan, George F., 1951. Realities of American ForeignPolicy, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Keohane, Robert O. and Joseph Nye, 1977. Power andIndependence: World Politics in Transition, Boston: HoughtonMiffin.

- ––– (ed.), 1986. Neorealism and Its Critics,New York: Columbia University Press.

- –––, 1989. International Institutions and State Power: Essays in International Relations Theory, Boulder: Westview.

- Korab-Karpowicz, W. Julian, 2006. “How InternationalRelations Theorists Can Benefit by Reading Thucydides,” TheMonist, 89(2): 231–43.

- –––, 2012. On History of Political Philosophy: Great Political Thinkers from Thucydides to Locke, New York: Routledge.

- –––, 2017. Tractatus Politico-Philosophicus: New Directions for the Development of Humankind, New York: Routledge.

- Lebow, Richard Ned, 2003. The Tragic Vision of Politics:Ethics, Interests and Orders, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Linklater, Andrew, 1990. Beyond Realism and Marxism: CriticalTheory and International Relations, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Machiavelli, Niccolò, 1531. The Discourses, 2vols., trans. Leslie J. Walker, London: Routledge, 1975.

- –––, 1515. The Prince, trans. HarveyC. Mansfield, Jr., Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1985.

- Mansfield, Harvey C. Jr., 1979. Machiavelli’s New Modesand Orders: A Study of the Discourses on Livy, Ithaca: CornellUniversity Press.

- –––, 1996. Machiavelli’s Virtue, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Maxwell, Mary, 1990. Morality among Nations: An EvolutionaryView, Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Mearsheimer, John J., 1990. “Back to the Future: Instabilityin Europe After the Cold War,” International Security,19: 5–49.

- –––, 2001. The Tragedy of Great PowerPolitics, New York: Norton.

- Meinecke, Friedrich, 1998. Machiavellism: The Doctrine ofRaison d’État in Modern History, trans. Douglas Scott. NewBrunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Molloy, Seán, 2003. “Realism: a problematic paradigm,” Security Dialogue, 34(1): 71–85.

- –––, 2006. The Hidden History of Realism. AGenealogy of Power Politics, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morgenthau, Hans J., 1946. Scientific Man Versus Power Politics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- –––, 1951. In Defense of the NationalInterest: A Critical Examination of American Foreign Policy, NewYork: Alfred A. Knopf.

- –––, 1954. Politics among Nations: TheStruggle for Power and Peace, 2nd ed., New York: AlfredA. Knopf.

- –––, 1962. “The Intellectual and PoliticalFunctions of a Theory of International Relations,”in Politics in the 20th Century, Vol. I, “The Declineof Democratic Politics,” Chicago: The University of ChicagoPress.

- –––, 1970. Truth and Power: Essays of aDecade, 1960–1970, New York: Praeger.

- Nardin, Terry and David R. Mapel, 1992. Traditions inInternational Ethics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nardin, Terry, forthcoming. “The New Realism and theOld,” Critical Review of International Social andPolitical Philosophy, first online 01 March 2017; doi:10.1080/13698230.2017.1293348

- Niebuhr, Reinhold, 1932. Moral Man and ImmoralSociety: AStudy of Ethics and Politics, NewYork: Charles Scriber’s Sons.

- –––, 1944. The Children of Light and theChildren of Darkness: A Vindication of Democracy and a Critique of ItsTraditional Defense, New York: Charles Scribner & Sons.

- Pocock, J. G. A., 1975. The Machiavellian Movement: FlorentinePolitical Thought and the Atlantic Political Tradition, Princeton:Princeton University Press.

- Rosenau, James N. and Marry Durfee, 1995. Thinking TheoryThoroughly: Coherent Approaches to an Incoherent World, Boulder:Westview.

- Russell, Greg, 1990. Hans J. Morgenthau and the Ethics ofAmerican Statecraft, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Sleat, Matt, 2010. “Bernard Williams and the possibility of a realist political theory,” European Journal of Political Philosophy, 9(4): 485–503.

- –––, 2013. Liberal Realism: A Realist Theory of Liberal Politics, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Smith, Steve, Ken Booth, and Marysia Zalewski (eds.), 1996.International Theory: Positivism and Beyond, Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- Scheuerman, William, 2011. The Realist Case for Global Reform, Cambridge:Polity.

- Thompson, Kenneth W., 1980. Masters of InternationalThought, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- –––, 1985. Moralism and Morality in Politicsand Diplomacy, Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War, trans. RexWarner, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1972.

- –––. On Justice, Power, and Human Nature: The Essence of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, Paul Woodruff (ed. and trans.), Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993.

- Vasquez, John A., 1998. The Power of Power Politics: From ClassicalRealism to Neotraditionalism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Waltz, Kenneth, 1979. Theory of International Politics,Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Walzer, Michael, 1977. Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argumentwith Historical Illustrations, New York: Basic Books.

- Wendt, Alexander, 1987. “Anarchy is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics,” InternationalOrganization, 46: 391–425.

- –––, 1999. Social Theory of International Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Weaver, Ole, 1996. “The Rise and the Fall of the Inter-Paradigm Debate,” in International Theory: Positivism and Beyond, Steven Smith, Ken Booth, and Marysia Zalewski (eds.), Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press, 149–185.

- Wight, Martin, 1991. International Theory: ThreeTraditions, Leicester: University of Leicester Press.

- Williams, Bernard, 1985. Ethics and the Limit of Philosophy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 2005. “Realism and Moralism in Political Theory,” in In the Beginning was the Deed: Realism and Moralism in Political Argument, ed. G. Hawthorn, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1–17.

- Williams, Mary Frances, 1998. Ethics in Thucydides: The Ancient Simplicity, Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Williams, Michael C., 2005. The Realist Tradition and the Limit of International Relations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 2007. Realism Reconsidered: The Legacy of Hans Morgenthau in International Relations, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wohlforth, William C., 2008. “Realism,” The Oxford Handbook of International Relations, Christian Reus-Smit and Duncan Snidal (eds.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- –––, 2011. “Gilpinian Realism and International Relations,” International Relations, 25(4): 499–511.

Academic Tools

| How to cite this entry. |

| Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society. |

| Look up this entry topic at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project(InPhO). |

| Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers, with links to its database. |

Actors In International Relations Ppt Presentation

Other Internet Resources

- Political Realism,entry the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Political Realism,entry in Wikipedia.

- Melian Dialogue,by Thucydides.

- The Prince,by Machiavelli.

- The Twenty Years’ Crisis(Chapter 4: The Harmony of Interests), by E.H. Carr.

- Principles of Realism,by H. Morgenthau.

- Peace and War,by Raymond Aron.

- Globalization and Governance, by Kenneth Waltz.

Related Entries

egoism | ethics: natural law tradition | game theory | Hobbes, Thomas: moral and political philosophy | justice: international distributive | liberalism | Machiavelli, Niccolò | sovereignty | war

Copyright © 2017 by

W. Julian Korab-Karpowicz<sopot_plato@hotmail.com>